Biomass: A Renewable Energy Source or a Danger to the Environment?

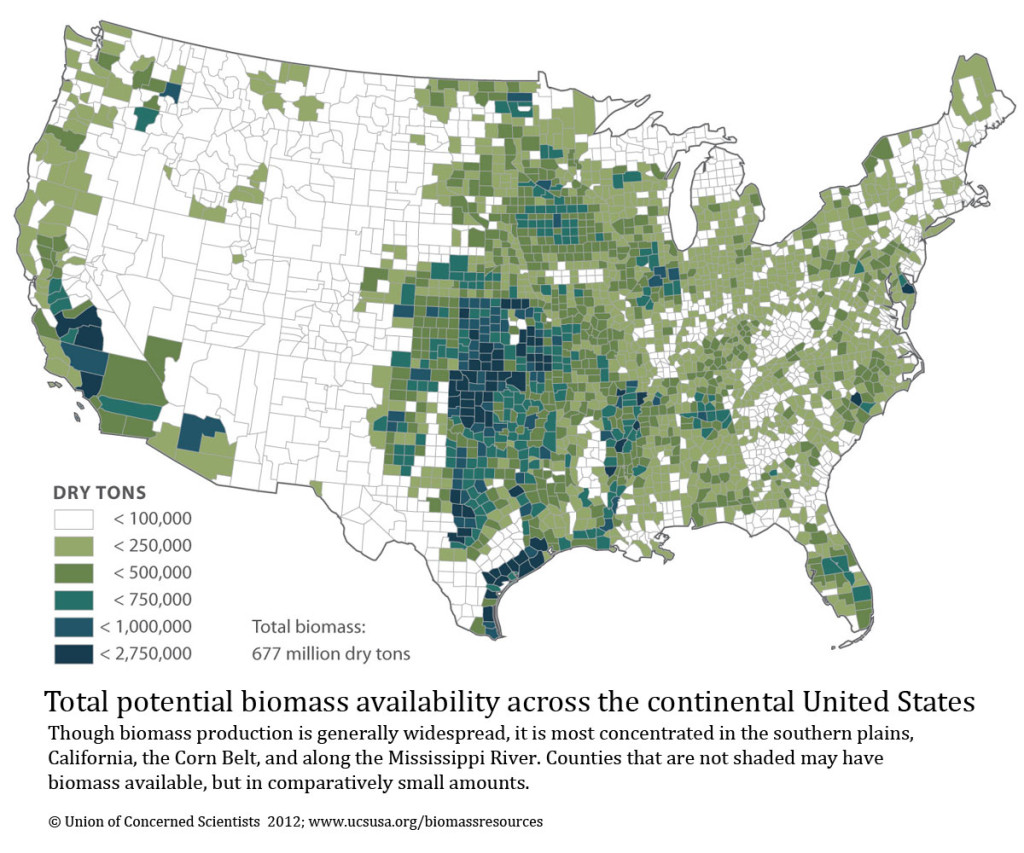

The biggest producers of biomass in the world are Canada and the United States, with over 50% of the global production, yet most North Americans don’t know what biomass is. Biomass is a new energy source seen as a viable alternative to fossil fuels, but the use of biomass has been a hot debate in recent years because of its potential danger to the environment.

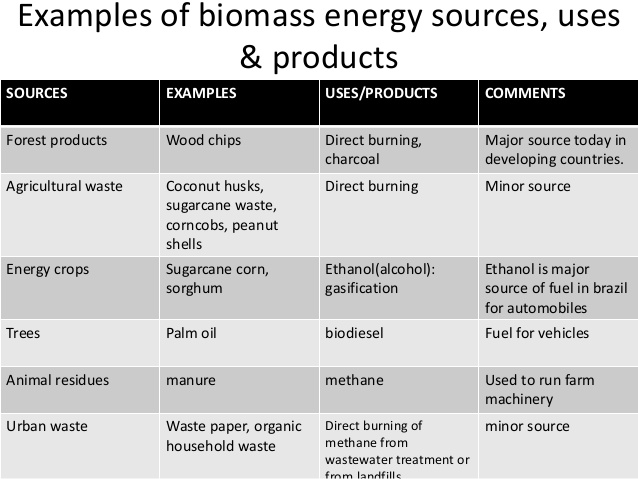

Biomass is organic material made from trees and plants that are living or recently dead. In Canada, for example, biomass can be collected from four origins: Primary biomass comes from forest industry by-products, such as leftover trees and branches, and trees affected by natural causes, like fires. Secondary biomass stems from industrial process by-products, such as wood chips. Tertiary biomass of leftovers from construction and renovation projects. Finally, quaternary biomass is made exclusively from trees produced in intensive silviculture.

All four kinds are then transformed to produce renewable bioenergy used as heat or biofuels such as biodiesel for use instead of gas. Biomass can also be used to create bioproducts, such as textiles, and industrial chemical bioproducts, such as glues.

Photo by Kyle Spradley | © 2014 – Curators of the University of Missouri

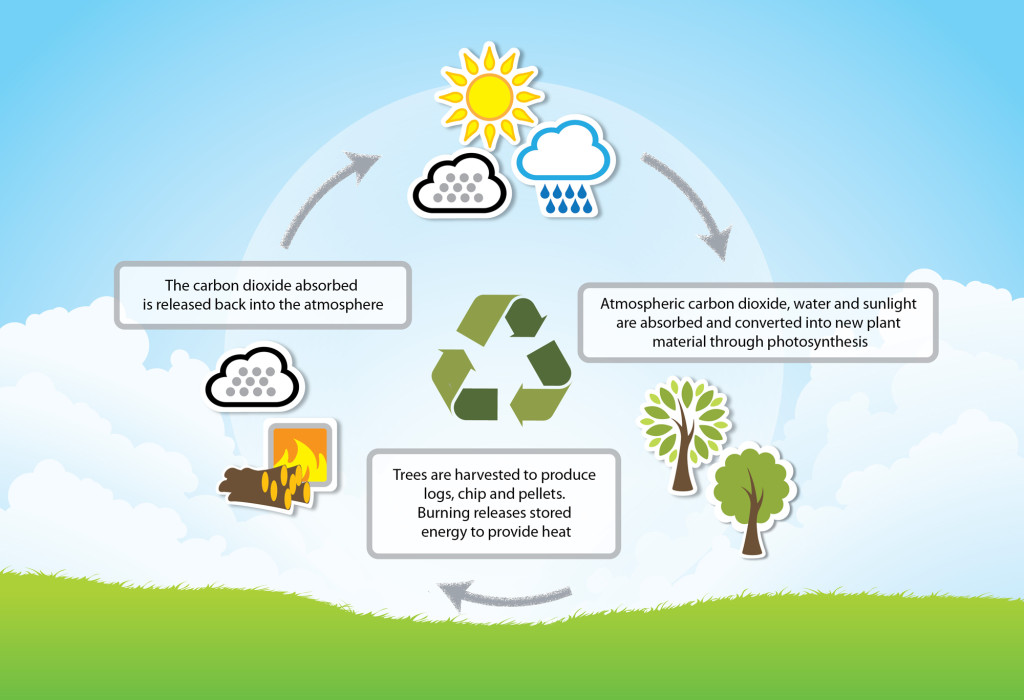

The biomass industry arose in the 1970s during the oil crisis as a more environmentally-friendly alternative to fossil fuels, with the main goal being to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. That being said, biomass gathering and use needs to be extremely meticulous if it doesn’t want to add more negative consequences to the environment, such as a lack of trees and thus lower amounts of CO2.

Is biomass a great energy alternative or a harmful option?

To find out, I called Nicolas Mansuy, 36, a researcher and analyst in forest biomass for Natural Resources Canada. He specializes in the boreal forest, which is Canada’s largest vegetation zone, covering up to 55% of the country’s land. Mansuy’s job is to make inventories of how external forces, such as problems brought on by humans and natural disruptions like fire and insects, affect the biomass available in the boreal forest.

It is fundamental, Mansuy explains, that a balance remain in the carbon ecosystem, so when trees are cut to produce biomass, other ones need to be planted immediately (which is what intensive silviculture is all about). The problem is that tree growth can take years. One solution to this issue is planting trees that grow quicker–like willows–allowing for trees to be replaced at a much faster rate.

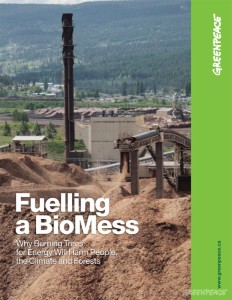

Despite the precautions taken by researchers such as Mansuy to limit the carbon offset of biomass production, Greenpeace has issued a lengthy document that argues against the benefits of biomass. It claims that biomass extraction endangers the environment and that, until trees finally grow back, it is not environmentally conscious. In fact, they call the venture “biomess.”

Greenpeace claims that CO2 emissions that emerge out of biomass power plants are harmful to people’s lungs due to carbon monoxide. In response, Mansuy claims that while biomass extraction in the short run can be more polluting than fossil fuels, in the long run it is beneficial because the forest is a renewable resource that will provide a constant CO2 payback for years to come.

Greenpeace claims that CO2 emissions that emerge out of biomass power plants are harmful to people’s lungs due to carbon monoxide. In response, Mansuy claims that while biomass extraction in the short run can be more polluting than fossil fuels, in the long run it is beneficial because the forest is a renewable resource that will provide a constant CO2 payback for years to come.

It is important to note that the payback varies by region, and as a result the biomass gathering and use might differ from place to place. The result is influenced by “the type of fossil fuel replaced, the conversion technology used and the forest growth rates,” according to Natural Resources Canada.

Biomass has the potential to be an eco-friendly fossil fuel alternative, but it is crucial that the industry takes many precautions. In fact, the Union of Concerned Scientists in the United States published a report in 2012 that boldly states that ‘‘biomass holds the promise of clean power and fuel – if handled correctly.’’

Massachusetts has been a world leader in biomass gathering due to strict regulations for biomass plants. On top of this, in September the Massachusetts Clean Energy Center announced a five-year commitment to boost the use of clean energy in households and businesses.

Outside of Massachusetts, the big problem in the industry is that there are no set rules and regulations on biomass gathering, transformation and use nationally or internationally. According to Ben Bell-Walker from the Biomass Energy Council, this “can only hamper the biomass industry’s growth and standing.”

However, Natural Resources Canada says that there are rules and regulations in place to ensure biomass is harvested responsibly and then regenerated–the problem lies in that those rules and regulations can vary, and the industry needs to become more standardized.

‘‘The key for the jump-start of the bioenergy industry is the grouping of experts and scientists to put together the data to facilitate decision-making,’’ says Mansuy.

Biomass specialists like Bell-Walker and Mansuy are working hard to make sure that the CO2 payback works evenly for many years to come. That being said, there is still a lot to be done in research and on the ground, because the biomass industry is still relatively new. It is important that biomass specialists continue finding newer and better solutions, such as the second generation of biofuels, and learning from the work and the research already done.