Cut to the chase: What exactly is austerity?

“Austerity” is a term we often hear bandied about in these cash-strapped times. It’s been getting a lot of recent publicity in Europe, particularly in Greece, but it’s also been affecting the US for several years now, too. Most of us probably have at least a cursory idea of what it means: governments cutting public services in order to reduce a “deficit”, which in layman’s terms means the government’s coffers are in the red and it owes money. But where do those debts come from, and why are we–-and not the people who built up these enormous debts in the first place-–paying the price?

To explain this, we need to go back to 2008 and look at a brief explanation of the US financial crisis. US stock market and capital spending had skyrocketed, and so interest rates were cut to 1% to avoid a recession. The financial services industry saw in this an opportunity to make money on real estate. The crux of the collapse was something called the subprime mortgage. Subprime mortgages were aimed at people who had bad credit ratings or no credit history. In a healthy housing market, when these people defaulted on their mortgages, the bank would receive a home which was rising in value. When the value of homes stopped rising, however, banks realized that they’d taken far too much of a risk in trading in these subprime mortgages. The bottom 40% of the US income distribution hasn’t had a real wage increase since 1979, so credit cards and loans were naturally commonplace, meaning that banks were in a real fix when this source of income began to dry up.

To explain this, we need to go back to 2008 and look at a brief explanation of the US financial crisis. US stock market and capital spending had skyrocketed, and so interest rates were cut to 1% to avoid a recession. The financial services industry saw in this an opportunity to make money on real estate. The crux of the collapse was something called the subprime mortgage. Subprime mortgages were aimed at people who had bad credit ratings or no credit history. In a healthy housing market, when these people defaulted on their mortgages, the bank would receive a home which was rising in value. When the value of homes stopped rising, however, banks realized that they’d taken far too much of a risk in trading in these subprime mortgages. The bottom 40% of the US income distribution hasn’t had a real wage increase since 1979, so credit cards and loans were naturally commonplace, meaning that banks were in a real fix when this source of income began to dry up.

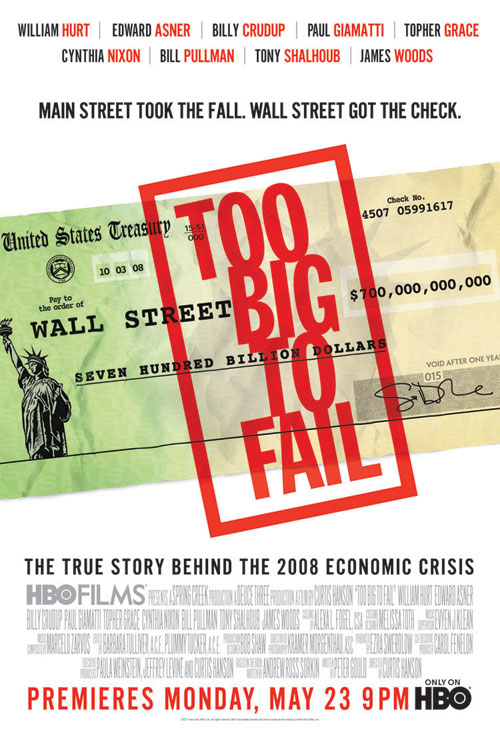

So what now? Enter government funds to bail the banks out, because these institutions were considered “too big to fail”. The Emergency Economic Stabilization Act of 2008 saw the US government spend around $700 billion on saving American banks from ruin. They then proceeded to start clawing back that $700 billion through cuts to public services, just as funds are being recovered in the UK, Greece and other European countries. Problem is, austerity measures have the counterproductive effect of bringing down GDP (gross domestic product), because they stall a country’s growth. GDP scores are a vital aspect of a country’s power and influence.

Greece is another good example to look at here, being the country currently worst-hit by austerity. Greece has been in deep water (sorry) for a while. Their economy was weak to start with, with no real industrial base of export materials. Alongside the 2004 Olympics, generous working conditions have been scapegoated as a main cause of its final plunge into financial ruin: public sector wages soared 50% between 1999 and 2007, and workers were granted “13th and 14th month” salaries–-in other words, double pay during the holidays. Underneath, however, lurks a story of corruption unconnected to the ordinary worker, with widespread tax evasion and fiddling of expenses rife amongst the more privileged classes.

In 2001, having been previously rejected in 1998, Greece became the 12th and last European country to join the Eurozone and adopt the Euro as its currency. This switch marked a huge increase in public spending. However, it emerged that reports on the country’s debt levels and deficits had been inaccurately reported by the Greek government, and Greece didn’t actually fulfill the GDP criteria needed to be part of the Eurozone. The country’s borrowing spiraled and by 2012, Greece had reached the highest sovereign debt default in history. Greece must pay the European Central Bank €3bn ($3.3bn) by August 20th of this year–money it simply doesn’t have.

Just this evening, it was announced that Greece had reached an €86bn ($95bn) outline agreement with creditors. If it goes ahead, this will be the country’s third bailout in five years. Despite the fact that it has been the result of intense discussions with Greek PM Tsipras and his government, the agreement will nevertheless impose more austerity cuts on an already ailing nation. Many supporters of Tsipras’s Syriza party are up in arms. Last month, over 61% of the Greek public voted to reject the terms of an earlier bailout deal, offered without negotiation. This vote lead many to fear a “Grexit”–that is, Greece leaving the EU. Despite Greece’s poor financial record, it’s still considered to hold an important position within the EU, at least in terms of bargaining power with other countries: for instance Russia, Iran and China, all of whom it enjoys a good relationship.

So that’s austerity. In a nutshell, the folks at the top get greedy, gamble and/or cheat, and then we pay. If that sounds like a raw deal, it’s because it is.