I’m Still Here: A Letter from 1995

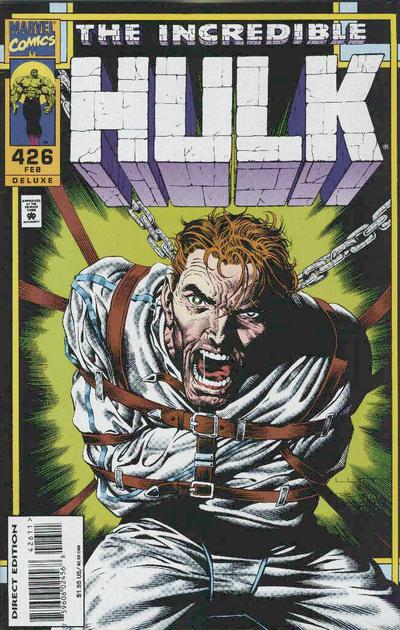

There’s one comic book I read as a kid that has haunted me ever since. It wasn’t because of the script or the art—although The Incredible Hulk #426 was an excellent story. It was reprinted in a ‘Best of Marvel’ anthology for 1995, which was a big deal in the days before every issue of a series was collected in trade paperback; in the ‘90s, the only way to read a previous issue, most of the time, was to buy an original back issue. These days, you can get it instantly through Marvel Unlimited, but you still won’t be able to read the part that left such a lasting impression on me.

Before message boards and social media, comic books used to have letters pages for fans to correspond with the creators. Like ‘letters to the editor’ in a newspaper, getting your letter approved by the publisher was a big deal. Future superstars like Todd McFarlane and Geoff Johns both had their first published work in comics appear in the letters columns. I was thrilled to have two letters printed in an issue of Batman. There wasn’t space for every comment, so your letter had to be publication-worthy, unlike the unmoderated comments sections on the internet today. And people actually had to read the books before they commented on them. The letters page was value-added content, never reprinted again. It not only connected readers with each other and the creative teams, it also documented a moment in time a few months prior.

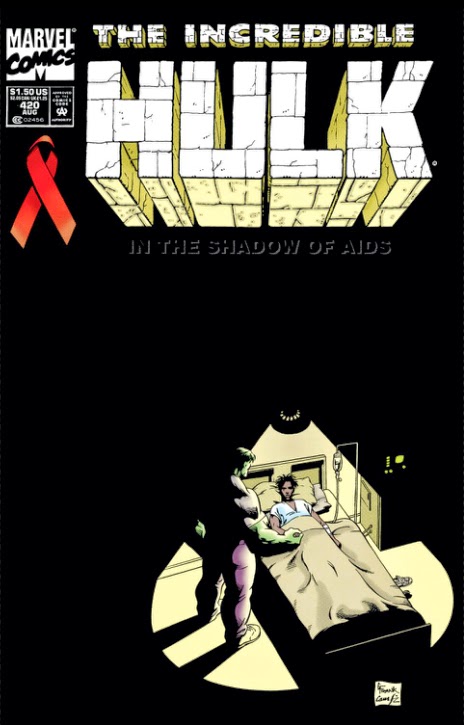

The responses in this particular book were to the controversial Incredible Hulk #420, in which the Hulk’s friend and former sidekick Jim Wilson (*spoiler*) died of complications from AIDS. Growing up in Wisconsin, I didn’t have any black friends, I didn’t know any homosexuals and I had certainly never met anybody with HIV. It had actually never occurred to me that black people could be gay, and the most I had learned about AIDS at this point came from this same comic book, sadly. This was an epic letters page–one of the letters actually came from transsexual activist Norrie May-Welby in Australia, who would later become world famous. But one letter stood out to me. Its introduction hit like the Hulk punching me in the gut:

“I am a 27-year-old black, gay male, surviving with full-blown AIDS.”

These words were penned by Kevin Frazier. His speech was loaded with raw emotion–anger, despair, helplessness; but also faith, hope and courage. Kevin was a real person, not just somebody my ignorant younger self would have defined by his race, sexuality or HIV status. He was upset at how the Hulk’s one black friend had disappeared from the book for three years after his diagnosis, only to die in his next appearance. He criticized Marvel’s erasure of Jim Wilson’s blackness and their refusal to acknowledge that he was also the Hulk’s gay friend. The most moving part, however, was Kevin’s determination to live:

“I hate the fact that the larger community cannot seem to respond to anything about this disease except death,” wrote Kevin. “And I, for one, am sick and tired of fighting what your grief does to me. It puts me in a box and seals my life off permanently. I love being part of life. Why are you so anxious to cut me out? I am still here.”

Struggling with what was at the time an untreatable, terminal illness, his plea to be accepted as a living human being was heartbreaking. Kevin signed off with: “This is my first letter to any publication. Please be gentle.” I don’t envy the editor who had to respond to Kevin’s printed letter.

Twenty years, hundreds of issues of the Hulk and several re-launches later–the world has changed considerably. The new generation is more tolerant of homosexuality. Bono has made AIDS a bipartisan cause. HIV is still a chronic illness, but no longer terminal if properly managed with medication. There’s now a prevention method called PrEP. Comic book companies no longer print letters and fans no longer mail them; DC Comics even stopped providing a message board in 2010. So ironically, my anonymous comments written as an adult, which I thought would last forever in cyberspace, are outlived by the old-fashioned letters of my youth.

Kevin Frazier’s letter lived on, too, crying out: “I am still here!” I thought about it off and on over the years, but didn’t actually dig the book out of the long box and polybag until after watching The Normal Heart on HBO, Larry Kramer’s semi-autobiographical depiction of the early years of the AIDS crisis in New York. Re-reading his letter again, with fresh eyes in the digital age, I noticed for the first time that not only were fans’ full names printed, but also their complete addresses. I could only imagine the types of letters Kevin had received in response. Publicly identifying oneself as both gay and HIV+ in the ‘90s must have taken a tremendous amount of courage. He was certainly the first person I had ever seen do so. I regretted not attempting to contact him before, since I had all the information I needed. Was he still alive and fighting? Was he still living in the same place? Did he still read Hulk comics? My curiosity led me to following his paper trail onto the internet to see what I could find.

Top search results were for a TV host who I quickly determined was not the same guy. Then, I saw a link for “Kevin L. Frazier ’89” at Amherst College, and thought this might be the one. Upon reading the first line, I knew that I was right: “Kevin Lawrence Frazier, Class of 1989, died on September 18, 2002, in New York City, from AIDS-related complications. He was thirty-five years old.” The Hulk had just punched me in the gut again.

Reading the obituary, I learned he had been an activist, produced plays and sang in the choir. Words from The Normal Heart echoed in my mind: “We’re losing an entire generation, young men at their beginning, just gone. Choreographers, playwrights, dancers, actors. All those plays won’t get written now, all those dances never to be danced.” I was overcome by a kind of survivor’s guilt. It seemed so unfair that he had died just a few years before antiretroviral therapy could have saved him. He and his longtime partner had to get by without any legal recognition of their relationship. Marvel had made a terrible Hulk movie, and then later made a better one. Green Arrow had an HIV-positive sidekick. Facebook. There were so many things I wished he had lived to see.

It was all public information, yet I felt creepy, as if I had invaded somebody’s personal space. It seemed like such an accident. Letters pages were never intended to enable somebody to stalk a total stranger from the other side of the country and pull up a street view of their front door on their computer. And a digital trail isn’t supposed to be traced from material that has never been digital. Only those of us with a foot in the print age, and another in the digital age, have a footprint in both.

This is not a cautionary tale about sharing too much personal information–the damage, if any, was already done years ago. Instead, this is comparable to the transition from oral to written history, in which the literate historians had an obligation to preserve the spoken history of the previous generation. Future generations won’t have an outlet to write to and a press to leave their mark in; their footprint is entirely virtual. We don’t have to worry about permanently losing our family photos in a house fire anymore. Our children will never know a time when their pictures weren’t on social media. We take for granted that new media can be streamed instantly while there are books, music and movies that have never been digitally preserved. Now we have an obligation to be the custodians of our generational, local, and familial history, particularly remembering people who were unable to do it themselves. Everybody has somebody’s untold story to tell, and it’s easier than ever to simply post those stories on a Throwback Thursday or Flashback Friday.

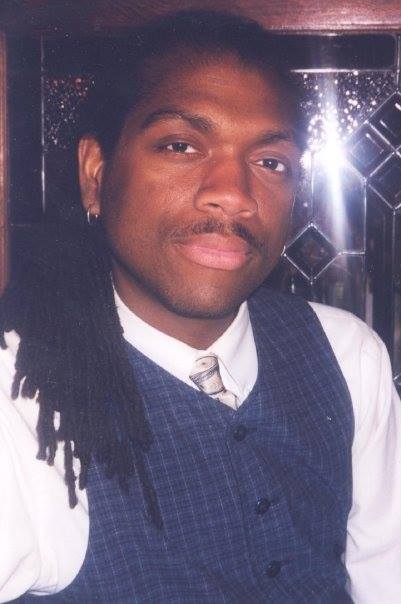

Through the miracle of the internet, I was able to connect with Kevin’s surviving partner, Francis Blacklock, who graciously answered some of my questions. Kevin had indeed received several letters from other readers, but no hate mail. They were all from other people living with HIV, writing to thank him. Faith in humanity renewed! He describes Kevin as, “An old soul, a very gentle person who was not afraid to be honest and challenge people. He did not see himself as a victim.” I found out Kevin had written his one-man show, Give Me Room, when he turned 30, because he didn’t think he would live to that age after he was diagnosed. Lastly, Francis shared a picture with me, so I could finally associate a human face with the letter.

In appreciation for the attention the media was giving to AIDS, Kevin had written “visibility equals life.” I can’t raise the dead, but I hope that by making his story visible, I can keep Kevin’s memory alive.